Moral Relativism: Differentiating Between Good And Evil

Morality is understood as a set of norms, beliefs, values and customs that guide people’s behavior (Stanford University, 2011). Morality will be the one that dictates what is right and what is wrong and will allow us to discriminate which actions or thoughts are correct or adequate and which are not. However, something that seems so clear on paper begins to raise doubts when we begin to dig deeper. An answer to these doubts and the apparent contradictions they generate is one that is based on moral relativism.

But morality is neither objective nor universal. Within the same culture we can find differences in morality, although they are usually less than those found between different cultures. Thus, if we compare the morals of two cultures, these differences can become much larger. In addition, within the same society, the coexistence of different religions can also show many differences (Rachels and Rachels, 2011).

Closely related to morality is the concept of ethics. Ethics (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) is the search for universal principles of morality (although there are authors who consider that ethics and morals are the same as Gustavo Bueno).

For this, those who study ethics analyze morality in different cultures in order to find what they share, which will be the universal principles. In the world, ethical conduct is officially included in the declaration of human rights.

Western moral

Years ago, Nietzsche (1996) crossed out Western morality as slave morality since he considered that the morality of resentful and of slaves because it considered that the highest actions could not be the work of men, but only of a God that we had projected outside of ourselves. This morality from which Nietzsche shunned is considered Judeo-Christian because of its origins.

In spite of the criticisms of the philosophers, this moral continues in force; although it presents some more liberal changes. Given colonialism and the dominance of the West in the world, Judeo-Christian morality is the most widespread. This fact, sometimes, can present problems.

This thought that considers that each culture has a moral is called cultural relativism. In this way, there are people who dismiss human rights in favor of other codes of good conduct, such as the Koran or the Vedas of Hindu culture (Santos, 2002).

Cultural relativism

Evaluating other morals from the point of view of our morals can be a totalizing practice: normally, when doing it from this point of view, the evaluation will be negative and stereotyped. For this reason, the morals that do not adapt to ours, almost always, we are going to reject, questioning even the moral abilities of people with another morality.

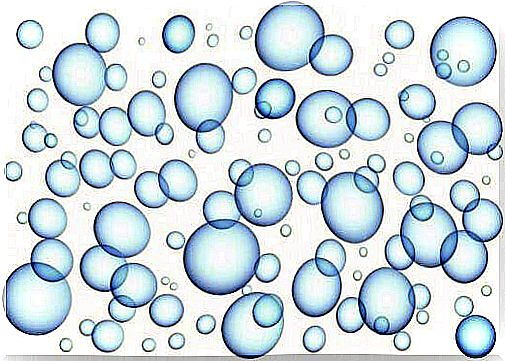

To understand how the various morals interact, we are going to take the explanations of Wittgenstein (1989). It explains morality with a very simple outline. To understand it better, you can do a simple exercise: take a sheet of paper and paint many circles. Each circle will represent a different morality. Regarding the relationships between the circles, there are three possibilities:

- That two given circles do not have any space in common.

- That a circle is within another circle.

- That two circles share a part of their common space, but not all.

Obviously, the fact that two circles share space will indicate that two morals have aspects in common. In addition, depending on the proportion of shared space, they will be more or less. In the same way that these circles, the different morals overlap, at the same time that they diverge in many positions. There are also larger circles that represent morals that integrate more norms and smaller ones that only refer to more specific aspects.

Moral relativism

However, there is another paradigm that proposes that there is no moral in every culture. From moral relativism, it is proposed that each person has a different morality (Lukes, 2011). Imagine that each circle in the diagram above is the moral of a person rather than the moral of a culture. From this belief, all morals are accepted regardless of who they come from or in what situation they occur. Within moral relativism there are three different positions:

- Descriptive moral relativism (Swoyer, 2003): this position defends that there are disagreements regarding the behaviors that are considered correct, even when the consequences of such behaviors are the same. Descriptive relativists do not necessarily defend tolerance of all behavior in light of such disagreement.

- Meta-ethical moral relativism (Gowans, 2015): according to this position, the truth or falsity of a judgment is not the same universally, so it cannot be said to be objective. The judgments are going to be relative when compared with the traditions, convictions, beliefs or practices of a human community.

- Normative moral relativism (Swoyer, 2003): from this position it is understood that there are no universal moral standards, therefore, other people cannot be judged. All behavior should be tolerated even when it is contrary to our beliefs.

The fact that a morality explains a greater range of behaviors or that more people agree with a specific morality does not imply that it is correct, but neither does it imply that it is not. From moral relativism it is assumed that there are various morals that will give rise to disagreements, which will not give rise to a conflict only if dialogue and understanding occurs (Santos, 2002). Thus, finding common ground is the best way to establish a healthy relationship, both between people and between cultures.

Bibliography

Gowans, C. (2015). Moral relativism. Stanford University. Link: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moral-relativism/#ForArg

Internet encyclopedia of philosophy. Link: http://www.iep.utm.edu/ethics

Lukes, S. (2011). Moral relativism. Barcelona: Paidós.

Nietzsche, FW (1996). On the Genealogy of Morality. Madrid: Editorial Alliance.

Rachels, J. Rachels, S. (2011). The elements of moral philosophy. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Santos, BS (2002). Towards a multicultural conception of human rights. The Other Right, (28), 59-83.

Stanford University (2011). “The definition of morality”. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Palo Alto: Stanford University.

Swoyer, C. (2003). Relativism. Stanford University. Link: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/relativism/#1.2

Wittgenstein, L. (1989). Conference on ethics. Barcelona: Paidós.