How Did The Jewish Holocaust Come To Be?

There are images that are proof of the level of evil that a society can reach. Anyone corresponding to Nazi Germany in which a Jew or a group of people of this religion appear can be a perfect example of this cruelty.

However, the question is still disturbing, what led a supposedly civilized society to support or ignore such a degree of dehumanization? How did the Jewish holocaust come to pass?

There may be no greater accomplice of immorality than the indifference of the rest and that indifference is protected by a multitude of phenomena explained by psychology.

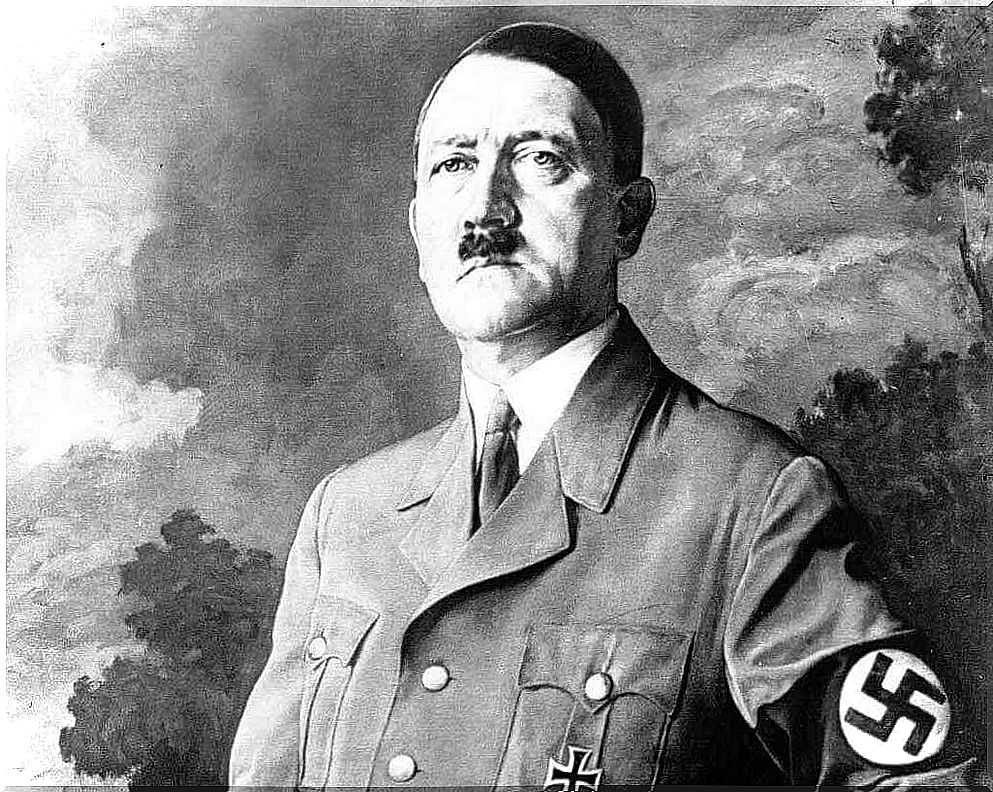

Hitler: a deeply frustrated man

An exciting event for counterfactual history (the one that speaks of what could have been and was not) is to suppose what would have happened if Adolf Hitler had not been rejected by the Vienna School of Fine Arts on two occasions (in 1907 and 1908) . The school excluded him, alluding to the fact that the young man suffered from “ineptitude for painting.”

This rejection of an institution, which he considered meritorious and superior, deeply damaged Hitler’s already wounded ego. Adolf directed all his anger towards the Jewish world, blaming them for all the calamities of Germany, and implicitly for his own, considering that some usurers and habitual traitors were leading his race, the “Aryan race” to ruin.

A discourse based on stereotype, prejudice and discrimination

We can say that Hitler and his supporters played their cards well, but if Germany had not still been paying the price for having lost World War I, history would have been different. A cost that was assumed by practically the entire country and that meant that all the product of the work was used to pay this debt.

Faced with the impotence of condemnation, Germany needed some guilty of its defeat whom it could defeat, to restore part of its pride. Hitler and his acolytes in their message were very clear about whom to point out, and the vast majority did not hesitate to massacre those people who had been targeted by the Nazi party.

The one who would be one of the greatest genociders in history established himself as the hero and savior of the people in a uniform, simple and direct speech. In a propaganda campaign created by Joseph Goebbels and which would be key in the triumph of Nazism, 11 principles were devised to explain to all the German people the problem that existed with the Jewish world.

Once again, the power of oratory and knowledge of the functioning of social behavior (other than individual) marked the course of history. Once again, knowledge and intelligence served evil, causing the Jewish holocaust.

Experiments that help us understand the Jewish holocaust

In genocide there is a perverse process of selecting people based on criteria such as race, religion or political beliefs; in this case everything that had to do with the Jewish world. The amount does not matter, their lives do not matter, their suffering does not even matter, because the greater this, the greater the supposed revenge.

Assuming this evil is difficult, but enduring indifference to this genocide is even more unbearable. How could the torture, overcrowding and systematic death of millions of people take place within old Europe? A Europe that, in theory, had fought for freedom for centuries and in which enlightenment and culture seemed to have triumphed.

Dehumanization in an extreme and hostile environment

Philip Zimbardo designed an experiment to study the influence of the environment on the behavior of the individual. Many people who had acted as jailers who had been asked, after they lost the war, why they did it, replied that they were simply obeying orders.

In other words, they were aware that they were simply playing their role, without wondering if it was right or wrong.

To understand how this was possible, Zimbardo selected 24 university volunteers and divided them into two groups. They were both going to live in a mock jail, but with a subtle difference: the members of one group were to be the jailers and the members of the other group were to be the prisoners.

Not even two days had passed when the group of guards began to observe behaviors of humiliation towards colleagues who had not done anything to them. Thus, those behaviors became so widespread and degrading that the experiment lasted just one week, when it had been scheduled for two.

Zimbardo managed, simply by granting a role, that normal university students in less than a week became real torturers. Imagine what the Nazi jailers could do with people they did not consider such, because they simply had a number assigned instead of a name, and who were considered to be the culprits of their misfortune.

This experiment showed that in extreme situations and with excess power, any of us can show undesirable behavior towards others, something similar to what happened in the Nazi concentration camps with the guards and prisoners.

Blind submission to authority

Stanley Milgram was also interested in what happened during the Jewish holocaust and also wondered how there had been blind obedience to the inhumane proposals of the Nazi leaders by German soldiers who had never shown violent behavior.

In Milgram’s experiment, there were three figures, two “friends” and another was the experimental subject. The framework was as follows: a so-called experimenter had devised an experiment that sought to test the effectiveness of punishment on learning. Said punishments were supposed shocks given through a machine and the real objective of the experiment, of course, false.

However, with this excuse, he asked different experimental subjects, who had volunteered, to punish a “buddy” of the experimenter himself each time he failed some questions they had to ask him.

The experimenter, to verify the alleged thesis, asked the volunteers to increase the voltage of the punishment discharge, gradually, each time the apprentices failed.

These trainees, of course, were good actors and each time the volunteer gave them a supposedly higher voltage shock they screamed and squirmed more. In this way, the volunteers came to give shocks of a voltage that would have ended the life of the apprentices.

How was it possible that normal subjects ended up killing people they had nothing against? Simply because the fact that there was a figure they considered to be of authority – the experimenter – had caused them to override their personal ethics. On the other hand, many also said that they had signed a commitment at the beginning of the experiment not to abandon it and this is what they kept.

Finally, the voltage of the discharges was gradually increasing, so that perhaps many of those who reached the highest voltage discharge would not have given it if it had been unique. However, on the scale, this discharge was only slightly stronger than the previous one.

Thus, many Germans also sealed their commitment to the cause, at first, the cruelty of Nazism was not so great. On the other hand, they also got rid of their personal ethics to subordinate themselves to that of their superiors, people who in some way, as the experimenter in the Milgran experiment, were also considered authority figures.

The helplessness learned from Jewish prisoners

Martin Seligman wanted to study how the Jewish holocaust could have happened, since the captives in concentration camps were far outnumbering their jailers and a well planned and organized revolution would have prevented the genocide from continuing.

Seligman in his experiment exposed two dogs locked in large cages to occasional electric shocks. One of the animals had the possibility of operating a lever with its muzzle to stop this discharge, while the other animal had no means to prevent this discharge.

When this second group of dogs were given the opportunity to escape the shocks, the animals remained still without showing any type of response. This state of inactivity was explained by the phenomenon of learned helplessness.

Learned helplessness consists precisely in a state in which the subject does not try to escape or avoid aversive stimuli – in this case it was shocks, but it could be any other – even if they have the opportunity to do so. Previous experience has taught them that whatever they do, they cannot avoid what is happening to them.